The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), signed into law on August 16, 2022, allows the federal government to negotiate prices for some high-cost drugs covered under Medicare. Under the law, many small molecule and biologic drugs that do not have approved and marketed generics or biosimilars, and that are among the 50 highest-spend Medicare covered drugs for each of Part B and D, can be eligible for negotiated prices nine years (small molecule) or 13 years (biologic) after FDA approval.[1]

There are some categories of drugs that are ineligible for negotiation, such as drugs with Medicare spending under $200 million/year, drugs with one orphan indication and no other indications, plasma-derived drugs, and some small biotech drugs (until 2029). If a biosimilar manufacturer applies for a delay (“Initial Delay Request”) in the selection of a reference product for inclusion on the negotiation list, it is possible that some biologic drugs with likely biosimilar market entry within two years will not be chosen for negotiation.

On August 29, 2023, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published the first list of drugs that will be subject to price negotiations. This first list includes drugs covered under Medicare Part D, with negotiations taking place in 2023 and 2024. The negotiated prices will be published by September 1, 2024, with the negotiated prices becoming effective January 1, 2026.

The drugs selected for the first set of negotiations are:

- Eliquis® (apixaban)

- Jardiance® (empagliflozin)

- Xarelto® (rivaroxaban)

- Januvia® (sitagliptin)

- Farxiga® (dapagliflozin)

- Entresto® (sacubitril/valsartan)

- Enbrel® (etanercept)

- Imbruvica® (ibrutinib)

- Stelara® (ustekinumab)

- Fiasp®; Fiasp® FlexTouch; Fiasp® PenFill; NovoLog®; NovoLog® FlexPen; NovoLog® PenFill (insulin aspart)

Under the IRA, the next list of drugs subject to price negotiations will include 15 additional Part D drugs for 2027, up to 15 more Part B and D drugs for 2028, and up to 20 additional Part B and D drugs each year after that.

According to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) guidance on the IRA provisions, prior to 2030 drugs will be put into two categories to determine the minimum discounts required during the negotiation. Long-monopoly drugs, which were approved more than 16 years prior to negotiation (on or before January 1, 2010), will be subject to a minimum discount of 60% on the non-federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP).

Short-monopoly drugs from 2026-2030 are all drugs not considered long-monopoly, and therefore those approved less than 16 years prior to negotiated prices taking effect. For the first list, this includes drugs that were approved after September 1, 2010 and before September 1, 2012 for biologics and September 1, 2016 for small molecules. They will be subject to at least a 25% discount on the non-FAMP.

Beginning with the 2030 drug pricing year, there will be a third category, extended-monopoly drugs, which will be subject to a minimum discount of 35% of the non-FAMP. This will be drugs approved between 12 and 16 years prior to the drug pricing year. Short-monopoly drugs will then be drugs less than 12 years since approval, and will only include small molecule drugs, as biologic drugs cannot be subject to price negotiations until they have been approved for at least 13 years.

If the companies with drugs chosen for negotiation choose not to comply with the negotiation process, the law provides for a penalty of an excise tax starting at 65% of US product sales, increasing up to 95%. Alternatively, the manufacturer can choose to withdraw all of their drugs from Medicare and Medicaid coverage. If the manufacturer negotiates a price but then charges more, they can be subject to penalties of 10 times the difference between the price they charged and the negotiated price.

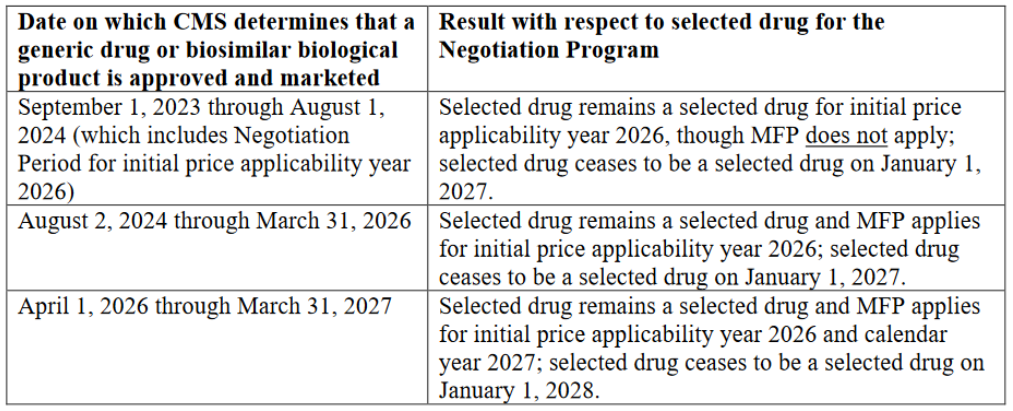

Drugs can be taken off the negotiation list once a generic or biosimilar is marketed. Eligibility will be monitored, and once a drug is no longer eligible, it will be taken off the next list, but will remain subject to the negotiated price for the remainder of the year. Depending on the timing of generic or biosimilar entry, the reference product could be subject to negotiated prices for almost two years after generic/biosimilar market entry.

The first list published by HHS includes three biologic drugs: Enbrel, Stelara, and Insulin Aspart (Fiasp and NovoLog).

Enbrel (etanercept)

Enbrel is one of the top selling drugs, with over $4 billion in global sales in 2022 (down from a peak of almost $6 billion in 2016). According to CMS, Medicare spent approximately $2.8 billion on Enbrel from June 2022 through May 2023.

Patent litigation wins for the reference product sponsor (RPS) have kept the two approved biosimilars, Erelzi® (etanercept-szzs) (approved in 2016) and Eticovo® (etanercept-ykro) (approved in 2019) off the market until patent expiry in April 2029.

Enbrel’s approval in 1998 will likely make it a long-monopoly drug, subject to a minimum discount of 60% during price negotiations. For this reason, it may be attractive to negotiate biosimilar entry prior to August 1, 2024. If a biosimilar is considered to be bona fide marketed by August 1, 2024, Enbrel would effectively remove itself from any negotiated price taking effect. Given that biosimilars so far have generally brought prices down in the US by less than 60%, it may be a beneficial strategy for Enbrel given there are approved biosimilars waiting to launch.

Stelara (ustekinumab)

Stelara is another top selling drug, with almost $10 billion in global sales in 2022. Medicare spent approximately $2.6 billion on Stelara from June 2022 through May 2023.

While there are no approved biosimilars in the US currently, there are at least three pending aBLAs, for ABP 654 (submitted to FDA in November 2022), AVT04 (January 2023) and CT-P43 (June 2023). Recently, numerous biosimilar settlement agreements have been signed allowing for launches starting January 1, 2025, if the biosimilars are approved. Should launches begin in 2025, it is possible Stelara will only remain on the negotiation list for 2026 and will cease to be a selected drug starting in 2027.

Should a biosimilar be approved prior to August 1, 2024, it is possible that settlement agreements could be renegotiated to allow for earlier launch. Similar to Enbrel, if a biosimilar is considered to be bona fide marketed by August 1, 2024, Stelara would still be considered a selected drug, but the negotiated price would not take effect.

Because Stelara was approved in September 2009, it will likely be considered a long-monopoly drug, subject to a minimum discount of 60%.

While it may be surprising to see Stelara on the list given the potential biosimilar launches in the next two years, and the ability for biosimilar manufacturers to request delay of inclusion of the reference product on the list if biosimilar launch is imminent, there may be some provisions of the Act that restricted the ability for an Initial Delay Request for Stelara. According to the Act (see CMS Guidance 30.3.1.1), biosimilar manufacturers can only submit a delay request for “extended-monopoly” drugs, that is drugs that have been approved for between 12 and 16 years prior to the start of initial negotiated prices on January 1, 2026. That means the reference product must have an initial licensure between January 1, 2010 and January 1, 2014. Given that Stelara was approved in September 2009, it is possible it was not eligible for the delay.

In order for a delay request to be granted, the biosimilar must provide clear and convincing evidence that there is a high likelihood that the biosimilar will be licensed and marketed before two years after the selected drug publication date. CMS considers whether patents related to the reference product are likely to prevent the biosimilar from being marketed in determining whether there is a high likelihood of marketing within that time frame. As of May 10, 2023, the date on which intent to submit a delay request had to be submitted to CMS for the 2026 price year, there was ongoing litigation over proposed biosimilar ABP 654. A request for stipulated dismissal due to settlement was not submitted to the court until May 23, 2023, and settlement agreements with other biosimilars were not announced until even later than this. Therefore, it is also possible any delay request that was filed could have been rejected because of patent protection.

It is also possible that the settlement agreements between the biosimilars and reference product sponsor allowing for launch in 2025 would have prevented any Initial Delay Requests from being approved under Section 1192(f)(2)(D)(iv) of the Act. This section requires that, for a delay request to be accepted, the biosimilar and RPS cannot have entered into an agreement that directly or indirectly restricts the quantity of the biosimilar that may be sold in the US any time on or after September 1, 2023. The guidance does not discuss whether patent settlement agreements specifying a future launch date would prevent the delay request from being granted.

Fiasp®; Fiasp® FlexTouch; Fiasp® PenFill; NovoLog®; NovoLog® FlexPen; NovoLog® PenFill (insulin aspart)

Fiasp and NovoLog are both insulin aspart formulations, differing in that the Fiasp formulation also includes vitamin B3. According to the Act, CMS aggregates data across dosage forms and strengths of an active ingredient with the same NDA/BLA holder, including new formulations, to determine whether a drug is eligible for negotiation. While there is an unbranded version of NovoLog available, for purposes of price negotiations under the Act, unbranded or authorized generic versions of drugs are not considered biosimilars that would remove a drug from eligibility for negotiation.

In June 2022-May 2023, Medicare spent a combined $2.6 billion on these drugs.

There are no currently approved biosimilars of the various versions of Fiasp and NovoLog; however there is at least one pending aBLA for a proposed NovoLog biosimilar, MYL-1601D (likely filed in 2021, with a Complete Response Letter from the FDA in January 2022).

NovoLog was approved in 2000, which would likely make it a long-monopoly drug subject to a minimum 60% discount. It is possible Fiasp will also be considered a long-monopoly drug despite approval in 2017 because it has the same active ingredient. The negotiations establish one maximum fair price (MFP) for the selected drug, which is not based on the formulation, that is computed across different dosage forms and strengths (see CMS Guidance 60.5).

Similar to Stelara, it is possible there were no delay requests from biosimilars because NovoLog is not an extended-monopoly drug. Biosimilars may also not have qualified for the provisions requiring that there be a high likelihood of approval and marketing within two years of the selected drug publication date.

It will be interesting to see how the negotiation process proceeds and how the outcomes of pending litigations challenging the applicable IRA provisions affect these and future negotiations.

[1] A drug can be included on the price negotiation list if at least seven or 11 years have elapsed between drug approval and the publication date of the list of selected drugs. Because there is a period of time between the publication of the list and when negotiated prices go into effect, the negotiated prices will not go into effect until at least nine or 13 years after FDA approval.

_________________________________________________________

The author wishes to thank April Breyer Menon for her contributions to this article.